Bute House – many people have never heard of it. Often nicknamed as Scotland’s 10 Downing Street, it is the name of the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland and is located at No. 6 Charlotte Square in Edinburgh’s New Town, as the centerpiece of Robert Adam’s final and finest example of urban architecture.

Unlike the world famous White House in Washington D.C. or No. 10 Downing Street in London which were more or less built for purpose (with major adaptations over the years), Bute House was built as a private home and it remained so until 1966, at which time when it was given over to the National Trust for Scotland. Only at that point was the building made available to officers of state as an official residence, initially for the Secretary of State for Scotland and latterly as the home of Scotland’s First Minister.

The only point of reference outside No. 6 Charlotte Sq which alludes to the building’s purpose are these well polished brass plates. Source: The Times Scotland

Due to the fact that only in recent times has the house come into use for its current role, the history of the building has been largely ignored. In the past 13 years the Scottish Cabinet has held regular meetings in the house, and as such it has become the scene of the making of some of the major decisions taken by Scotland’s devolved government. So, as the years go by this building will become more and more a part of the fabric of Scotland’s long and rich history and as such it merits having some of its own story being told.

Historical Background to Bute House

For a start, Bute House is not a term which would have been familiar to the people who constructed the building, it is a term which the house became known by in the 20th century, for which an explanation will be given later. Simply it would have been referred to as No. 6 Charlotte Square, one of 48 houses which were planned in the square which was to be the completing component of the first phase of the New Town.

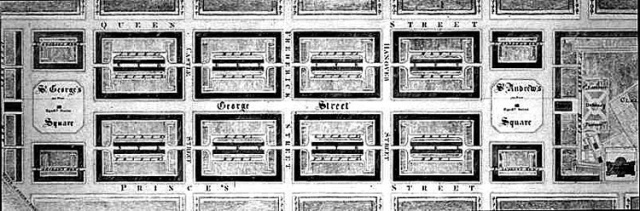

It could be said that the history of the house begins, at an embryonic stage, in the year 1768. There was no trace of a construction site, but there was a plan, drawn up by a young, unknown architect called James Craig. He had won the competition held by the Town Council in 1766 to come up with a design for a new town to be built for Edinburgh’s polite society to house itself in stylish townhouses and less overcrowded spaces as they had had to endure in the Old Town.

Craig’s plan of 1768 merely puts down on paper for the first time the future location of the house in his great scheme. Much would change between this conceptual idea and the commencing of building work on the house in 1792.

Firstly the name of the square itself would change, had the name on the 1768 plan stuck then I would be writing about No. 6 St George Square’. It had been so named as a counter balance to St Andrew Square at the east end of the New Town. St Andrew and St George being the patron saints of Scotland and England respectively, this being partly political in implication was intended to show that Scotland in the aftermath of the Jacobite uprisings of 1715 and 1745 was now fully reconciled to the Act of Union which had joined the two countries together in 1707, forming Great Britain. Other such overtures to the union were made in Craig’s original plan, and came to fruition Thistle Street and Rose Street being the national flowers of both Scotland and England again emphasising the togetherness of Britain.

St George Square never did come to pass, it was thought by some that the fact that Edinburgh already had a George Square located on the then southern outskirts of the city, that some confusion may be caused. Therefore a new name was needed, and the patron saint of England lost his place in the grand designs of Scotland’s capital city. If it wasn’t to be a saint, then like the rest of the New Town streets it would be named after a member of the ruling Hanoverian dynasty, King George III’s wife was chosen and became the only royal to be represented twice in the New Town, Queen Street had been so named in honour of Queen Charlotte and now Charlotte Square as well.

Another major alteration to the initial plan was due to the existence immediately north of Charlotte Square of the extensive Moray Estate, owned by the Earl of Moray and used as his private pleasure grounds. Craig had originally intended for Queen Street to be extended westwards behind the north side of the square, this mirrors what actually did happen at Queens Street’s east end where its runs behind the north side of St Andrew Square. And as at the St Andrew Square end there were to be mews lanes between the houses for the keeping of horses and carriages owned by the residents. But it turned out that the land needed for the north-west corner of Charlotte Sq. was part of Lord Moray’s property.

This fact almost put paid to the entire idea of a square at the west end of the New Town. The plan was no longer seen as practical due to the necessary encroachment onto Lord Moray’s land and instead the Lord Provost of Edinburgh declared that instead a circus or crescent should be considered which would literally have taken the edge of the plan and allowed building to commence without imposing on the Moray estate. The Town Council decided not to give up quite as easily as that though and entered into negotiations with the Earl of Moray to see what compromise could be made if any. The Earl agreed that the construction of the square could go ahead, however no mews were to be built at the rear of the north side and Queen Street would be cut short east of the square.

This turn of events was actually a blessing, as what it afforded the early occupants of the north front of Charlotte Square was the pleasant prospect of an uninterrupted “country scene” overlooking the Moray estate and villages such as Stockbridge down to the banks of the Firth of Forth and over to Fife. This also allowed for larger gardens at the rear of the houses than had been intended as they ran on to meet the edge of the Moray property. The estate boundary ran at an angle from east to west behind the square and so the gardens of numbers 9, 10 and 11 Charlotte Square at the west end of the north side of the square had far shorter gardens than did 1,2 and 3 at the other end of the block. Being right in the middle of the façade No. 6 had the median sized garden.

So, with all of these initial issues seemingly resolved the Town Council decided that the New Town needed to be finished with a great architectural triumph as some people had criticised the plainness of what had already been built from St. Andrew Square and along Princes, George and Queen Streets. To answer these complaints the council, commissioned that virtuoso Scottish architect, Robert Adam to design the facades for Charlotte Sq. in 1791.

Adam produced a unified scheme for the houses on the square; this was something completely novel for Edinburgh. The north and south sides were to be mirror images of the other and they became known as, “palace fronts”, and meaning that although they were made up of eleven individual houses these frontages were pulled together by their skilful design to appear as one grand edifice. No. 6 being the grandest of them all was the classically inspired centre piece to this harmonious plan, at 32 feet wide it was to be largest house in the block.

It was the north side of the square upon which work was to commence first; it would appear that amongst the very first feus taken for the square was that of the land for No. 6. In 1792 Orlando Hart purchased the feu for £290 (£348,000 in 2010).

Hart was a product of the new era of personal advancement that came with the 18th century economic boom. Starting out as a shoemaker he rose to become a City Councillor, member of the board of the public dispensary, captain of a golf club, and was nominated to represent the city of Edinburgh at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1777. It says something about Edinburgh’s consumer driven society when a man who began as a shoemaker is able to become wealthy enough to enter the city’s “gold rush” of the 18th century which was the speculative building of elegant townhouses.

Hart had to pay 5 guineas for a detailed copy of the elevation of the building and his builders were required to stick rigidly to the plan. Sadly, Hart did not live to see his latest money maker come to fruition as he died in Edinburgh in September 1793. His eldest son sold the house upon its completion to its first owner in c1796.

The finished result produced a house of four floors, the top floor being behind a pediment with sloped roofs and a basement below it all. In terms of the exterior; the basement level stonework was finished in a rock face style, above on the ground floor was a rusticated look, the first and second floors are polished ashlar, complimented with four Corinthian pilasters and a central, arched faux-venetian window above the front door, with stone carved roundels above the flanking bays on the first floor. The rear of the house, which, at the time of construction looked out onto a practically rural setting was ignored as far as finely polished stonework was concerned, it is more simply finished in exposed rubble.

The most unusual aspect of this house compared with other Georgian townhouses was the fact that it had a door in the centre of the building. Most of these homes had a door placed on the same side as the staircase, but that was impossible here for the sake of the symmetry of Adam’s “palace front” design. This led to a considerably altered ground floor plan compared to its neighbours. A T-plan entrance hall with two small rooms either side led through to the stone staircase with iron baluster. Also on the ground floor were a large dining room and a smaller service room at the rear of the house, overlooking the back garden and the Moray estate.

From the ground floor the stone stair leads down to the basement which would have been equipped with a kitchen and other rooms for the use of the servants in the house, storage space, laundry, scullery, wine cellar would all have been present at the time of construction.

Far above on the first floor, the entertainment floor, there were only three rooms; the large rectangle drawing room occupied the entire with of the house with its three windows overlooking the square. Connected to the main drawing room was the back drawing room, another large rectangle space. Adjacent to the back drawing room was a smaller parlour, all three of these rooms with ceilings of over 14 feet in height.

The second floor was where the principle bedrooms and dressing rooms were located and these would have been built of generous proportions. The third floor contained smaller bedrooms with sloping ceilings which would have been mainly earmarked for children and servants to live in.

In an age when maidservants would share beds these houses would be able to accommodate a surprising number of household servants as well as the large families which often occupied them. Staff and trades people were able to come and go from the house by going down the external area steps from the street and using their own door directly below the main entrance on ground level. Also in the servants area there was access through low wooden doors to storage space located underneath pavement, these still exist today and would originally have been used for coal and other household essentials.

Once the house was complete and sold by the Orlando Hart’s son all it needed was inhabitants to make the house a home, and by 1797 the first of them was in situ at No. 6 Charlotte Square.

Early Residents of No. 6

One of the first recorded inhabitants of the house appears to be John Innes Crawford Esq. who appears on the Edinburgh postal directory of 1797 at this address. His next door neighbour at No. 5 was John Grant of Rothimurchus, the father of the renowned diarist Elizabeth Grant who was born in that house. On the other side at No. 7 is John Lamont of Lamont an Argyllshire land owner member of the Royal Company of Archers. It is unclear what Crawford paid for the house but Lamont purchased No. 7 in June 1796 for £1,800 (£1.9 million in 2010), although slightly smaller than No. 6 is a reasonable bench mark figure for what these houses were selling for to their initial buyers, No. 4 was sold in 1797 for a similar figure.

John Innes Crawford was born c.1770 at Cleghorn House in Lanarkshire, a home which he inherited and it was no doubt from this base of membership of the landed gentry that he funded his life in Edinburgh.

Crawford was a man of scientific interest as in 1818 long after he left Charlotte Sq. he was elected to become a member of the Wernerian Natural History Society, based in Edinburgh it hosted many prominent scientists of the day.

Continuing to look through the post office directory for 1797 we see that a Mrs Alex Simpson is also noted as living at No. 6 Charlotte Sq. it is not clear what the arrangement is here. Being listed as she is suggests that she is widowed, as it would be her husband’s name which appeared on the list otherwise. She may have been a lodger in the house, or a housekeeper who had herself added to the directory, information on her is almost non-existent so all is supposition.

By the time the next postal directory for the city was published for 1799-1800, Crawford was still in situ at the house. In 1799 Crawford was married to Jean McMurdo, the daughter of John McMurdo of Drumlanrig who had been the Chamberlain to the Duke of Queensberry until he retired in 1799.

Jean was the subject of Robert Burns’ poem Bonnie Jean; Burns was a good friend of Jean’s family and a frequent visitor to their home on the Drumlanrig estate. At the time of their marriage John was a captain in the North British Militia.

Mrs Simpson did not appear on the 1799 directory but curiously she reappeared in 1800, and by this point Crawford and his Bonnie Jean had moved on. This was to be Mrs Simpson’s final year in the square and thereafter the house had new owners.

Early 19th Century Charlotte Square, the north-east corner, Source: Scotlands Places

In May 1805, a sale of the contents of the house is advertised in the Caledonian Mercury newspaper being sold by a Mr William Bruce who was an auctioneer. The possible owner at the time was a John Boyd Esq. who is known to have lived in Charlotte Square at the time, and the occupants of most of the other available properties were known. This sale came only one year before No. 6 was sold to its most famous early occupant, Sir John Sinclair.

Sir John Sinclair

Sir John Sinclair Bt. of Ulbster in Caithness became the owner of the house in 1806, there appears to be no newspaper advertisement for the sale, so it was likely purchased by private bargain. Sir John did not have far to flit, prior to No. 6 he was living only three doors away at No. 9 Charlotte Square. To go to this bother proves that there was status value in being the owner of the large house in the middle of the block rather than more architecturally simple and slightly smaller house a few feet away.

Sir John Sinclair. Source: BBC: Your paintings, uncovering the nations art collection.

Sir John was born at Thurso Castle in Caithness in 1754, the eldest son of George Sinclair of Ulbster and distantly related of the Earls of Caithness. He was extremely well educated as all Scotsmen of rank and position were expected to be through the course of the enlightenment, studying at Edinburgh University, Trinity College, Oxford; he finished up receiving his LL.D from Glasgow in 1788. In Scotland he was admitted as a member of the Faculty of Advocates and he was called to the English bar but he never practised law as a profession.

His first permanent addresses in Edinburgh had been in the Old Town and Canongate, but as with most persons of quality he was to vacate and move north across the by then drained Nor’ Loch valley and into the New Town. Homes in the Old Town being abandoned by the fashionable set were occupied by the lower orders and by the turn of the century that part of Edinburgh’s former grandeur was seemingly gone forever as increasingly the place became one great slum.

In the same year that he was created a baronet, 1780, he also entered politics. From his first election victory until 1811 he sat as MP for Caithness, a seat which was ‘inherited’ by his son, George who sat in the House of Commons until 1841, a total of 61 years between father and son.

Outside of parliament he was the founder of the Board of Agriculture, the ancestor body of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. As well as this he was he was a respected economist and financier, in 1784 he published his History of the Public Revenue of the British Empire which established his reputation. Leading on from this he became so trusted in his financial judgement that even William Pitt, a Tory Prime Minister took his advice on economic matters.

None of the aforementioned achievements are really what Sir John is remembered for. He is most famous by far as the pioneer who organised and compiled the First (or Old) Statistical Account of Scotland which published between 1791 and 1792. This feat was carried out by Sir John sending out requests in 1790 to over 900 parish ministers around Scotland. These ministers covered Scotland in its entirety and they were asked to answer a mere 160 questions to which Sir John desired answers. The questions were split up into four sections, geography and topography, population, agriculture and industry and then a selection of miscellaneous inquiries. Some of these participating clergymen were eminent scholars in their own right and their responses to this national survey were extremely detailed and well written. Through this huge undertaking of compiling and distilling these hand written returns Sir John created quite simply one of the most important documents in late 18th century Europe, an invaluable resource which extensively details the life of the people through the agricultural and industrial revolutions. Most recently the Third Statistical Account of Scotland was published between 1951 and 1992, an even wider ranging study but based on the principles of Sir John’s 18th century original.

Sir John’s occupation of the house came to an end in 1816 when he sold the property to the Edinburgh hotelier Charles Oman. Sir John moved a little further than he had in his previous flitting, but not by much. Setting up home for the final time he ended his days at 133 George Street, barley a stone’s throw from Charlotte Square, nowadays the site of Brown’s Bar and Brasserie.

Even in his retirement Sir John was still very active in the political sphere. An arch unionist, in 1828, he was writing counterblasts to newspaper articles, warning their readers of the danger of the proposed dissolution of union between Ireland and Great Britain. Despite the fact that he admitted Scotland would be more equally represented in Westminster by the departure of the Irish members, it failed to stop him from talking up the union mostly on the emotional ideal of the integrity of the British Empire, regardless of the feelings of a large part of the Irish populace.

Sir John died a few days before Christmas 1835 and his funeral was held in early January the next year and he was interred at Holyrood Abbey.

Oman’s Hotel

Charles Oman and his wife already kept hotels in the city at 22 St Andrew Street (known as Oman’s London Hotel) and 29 West Register Street (Oman’s Tavern Hotel). Their 1816 purchase of No. 6 Charlotte Square was not in order to set them up as patrician dwellers of Edinburgh’s most fashionable des res. No, they were there in what was to be an early example of the encroachment of commerce into the square, which in later centuries would almost entirely push out the residential character of these townhouses altogether. And what a prize to gain, if Charlotte Sq. was the New Town’s crowning glory, then No. 6 was the jewel in that crown as far as the houses went.

Back in 1806 Oman had been divesting himself of an hotel and tavern located at the back of St Andrew Sq. in a lane for £2,800 (more than £2.2 million in terms of 2010 earnings). He was obviously the budding businessman who was out to make his mark, buying and selling, moving up the property ladder as he went, to be able to secure a spot in Charlotte Square ten years later. There was money to be made in his line of business too, more visitors than ever were coming to Edinburgh to admire its newly constructed edifices, enjoy the shopping opportunities and theatre going.

Presumably one of the first changes that Oman made to the house was the attachment to the front of the building of the Oman’s Hotel signage. There are still markings visible today on the ashlar stonework belt between the ground and first floors, directly above the front door where that sign was once attached.

By the 1820’s No. 4 was also owned by Oman and this was added to his empire as an appendage to No. 6 doubling the size of his business footprint on the square, and matching the size of the Roxburgh Hotel as it was then only two townhouses also.

Not satisfied with taking on No. 6 in 1816, by that same year Oman was also renting and running the Waterloo Hotel on the Regent Bridge. This was Edinburgh’s first purpose built hotel and its, “extensive accommodation was decorated and furnished in such style and elegance as to surpass anything of the like in Britain,” according the, The new picture of Edinburgh for 1816. There was an associated coffee house, tavern and reading rooms for the use of guests or the paying public.

By 1816 Oman had become so renowned in the city for his, “knowledge in the culinary art,” that it, “has secured him the furnishing of most of the public dinners given in the city,” again repeating the words of, The new picture of Edinburgh for 1816.

With these very significant 1816 additions to his hotel empire and his growing reputation as a master of cuisine he became the undoubted “hotel king” in the city, Edinburgh’s early 19th century answer to the Hiltons perhaps? His hotels around the city became heavily patronised by the Scots aristocracy who no longer maintained an Edinburgh house in favour of a London address, and other distinguished visitors to the city. The arrival of guests at his hotels was often published in the papers of the time, and they were always listed in order of precedence. The published guest lists over the years reads like a list of Scottish peerage titles, Dukes and Duchesses of Argyll and of Atholl, Marquises and Marchionesses of Lothian and of Tweeddale, Earls and Countesses of Airlie, of Leven, of Rosslyn etc.

Oman diversified in a surprisingly modern fashion into hosting weddings at his hotels, as there is an example noted in The Scots Magazine of January 1822 of a wedding of Mr Thomas Mather to Sarah Maria Eastey which took place in the future Bute House. Also, corporate entertainment as it would be termed now was a feature of the business, on the 1st of June 1822 the 20th Anniversary meeting of the Didactic Society took place with dinner on the table for 5pm. These events took place in the same year as the royal visit of the King, and this would have been most likely the most profitable year of Oman’s life as Edinburgh teamed with incomers from all over the place.

Oman’s Waterloo Hotel occupied the left hand side of Waterloo Place, it still exists as the Apex Hotel. Source: Scotland’s Places.

It was at No. 6 Charlotte Sq. that Charles Oman died in early August 1825, this however was not to be the end of Oman’s Hotels in Edinburgh. Mrs Oman now widowed, endeavored to carry on in the absence of her entrepreneurial husband and she proved that the highest born types of visitor were still keen to patronise their establishments. The hotel empire was downsized upon her husband’s death, she did not keep the lease to the Waterloo Hotel and so it was rented to a Mr Gibb shortly after Charles Oman’s death. Sadly for Mrs Oman, her eldest son had died in Jamaica in 1819 and so life may have been somewhat lonely for her depending on how close at hand other family members were.

Keeping the family owned part of the business going would have given her great focus, in preserving her husband’s legacy she could honour his memory. In 1832 Mrs Oman oversaw the arrival of the hotel’s most famous guest to date. From February that year King Charles X of France (youngest brother of King Louis XVI) and his court in exile were temporarily removed from the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which they had been allowed to stay in by King William IV since the former King’s arrival in Britain following the loss of his throne in the July Revolution of 1830.

King Charles X of France, seen here in his coronation robes in 1825 reigned from 1824 until the July Revolution of 1830.

Twice in his life had he become an émigré, and twice he spent a part of that exile in Edinburgh.

As the Comte d’Artois, he was in Edinburg, living at Holyrood Palace in the 1790’s in the after math of the execution of his brother and sister in law; Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Upon the downfall of Napoleon I in 1814 the Bourbon’s were restored to the French throne under King Louis XVIII, Charles elder surviving brother. Upon Louis’s death in 1824, Charles became King. An absolutist to the core he attempted to reverse the French Revolution and restore the Ancien Regime. This led to the 1830 July Revolution, and the King found himself back in Edinburgh and for a time at Oman’s Hotel.

Source: Wikipedia

The French royal party who were mostly born at the Palace of Versailles into the world of Ancien Regime politics espousing absolute monarchy, excused and upheld by the Catholic Church; found a warm welcome in Edinburgh from the intensely anti-absolutist and staunchly Protestant Scots. Perhaps they were delighted to see royalty of any nationality frequenting their capital city as King George IV’s visit ten years earlier had been the first ever visit of a British monarch to Scotland. Prior to that the most recent visit of a Scottish King had been in 1633 when very reluctantly, Charles I made a visit to Edinburgh for his coronation. Although having been born in Scotland and speaking with a Scottish accent the King, who was also the English monarch chose to base himself permanently in England, it would seem that the latter nations Anglican faith sat far easier with the Catholic inclined Stuart monarchy.

Presumably the King Charles X’s royal entourage took up both Nos. 6 and 4 Charlotte Sq. as they booked out Oman’s Hotel in Charlotte Sq. in its entirety. One would assume that the French King would have been lodged in the principal house No. 6 and allowed his flunkeys and hangers on to find room in the appendage property.

Mrs Oman continued receiving her high born guests at Charlotte Square into the 1840’s. The first year of that decade royal wedding fever swept across Britain, the young Queen Victoria was to marry her cousin Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Mrs Oman joined in the party atmosphere and many houses were illuminated with lit up stars, crowns and VA initials burning in oil lit lamps. Mrs Oman had two stars illuminated outside No. 6 and lists were published in the newspapers to let the public know where to walk around to see these lit up displays.

Interestingly, Mrs Oman is alive long enough to appear on the 1841 census which is the first useful census to be taken in the British Isles. Mrs Oman is revealed for the first time as, Grace Oman. Grace is 60 years of age and living in No. 6 Charlotte Square with three others. Donald Mcglashan is her 40 year old waiter, and they are joined by two younger female servants, Caroline Remp, 25 and Isabella Morrison, 20.

In October 1844 Grace Oman died at No. 6 from having, “water on the chest” which was attested to in the parish records. Listed as 68, this is probably her true age as a close feirnd or relative would have reported it. She obviously decided to round her age down in the 1841 census, from 65 to 60, and this was not an uncommon lie in an age of sketchy records at best where nobody was ever going to catch you out.

New Money Returns No.6 to Private Use

By 1845 No. 6 had been sold off by Grace Oman’s heirs to Alexander Campbell, No. 4 had also gone its own separate way and been sold to one James Brown. Alexander Campbell was aged around 37 years old when he moved into No. 6 and we are afforded a closer look at his family and servants over the years of his occupancy from examining the census returns.

Alexander was the son of Archibald Campbell the brewer and he was born in Edinburgh around 1808. In 1851 Alexander is given as being 43 years of age, and he has inherited the brewery of his father. Campbell’s wife Catherine aged 37 and their children; Catherine 12, Alexander 10, Maurice 9, Elizabeth 6 and John 2. All of the family were born in Edinburgh.

They were looked after by a modest household staff of 4 servants, all female. The eldest amongst these was Margaret Aitkenson 31, she is listed as the cook, but in practice she would probably have doubled up as a sort of housekeeper to help Mrs Campbell look after the running of the house.

Born in the Scottish Highlands in Ross-shire, she would most likely have been the daughter of crofters who had in recent decades been cleared from the land to make way for sheep, and the profits of the wool trade. Famously many of the victims of the Highland Clearances fled from Scotland to Canada, the United States and further afield still, but many also stayed in Scotland and moved into the expanding towns and cities of the central belt. In Glasgow they were put to work in one of the many industrial works which that city was becoming world renowned for, in the far less industrialised Edinburgh these highlanders were swallowed up by the insatiable demand for domestic servants in the homes of the wealthy.

Margaret Aitkenson was joined on the staff by; Elizabeth Glover, 26 from Edinburgh, Jane Milne, also 26 and from Edinburgh and finally Margaret Dickson aged 27, she came from Kelso in the Scottish Borders. All of these young women were listed simply as house servants without giving them more specific job titles.

An emigration document relating to Elizabeth Glover dating from 1857 shows her leaving Scotland and sailing for Australia when she was 32. Elizabeth was joined by her widowed mother, aged 52. Elizabeth’s sisters Euphemia 30 and Helen 24 were also accompanying them as was their younger brother John aged 13. The family travelled aboard the Monica and the voyage would have taken between 2 and 5 months depending on the conditions encountered and the experience of the crew. The document also takes note of the family’s religion, Protestant; and whether or not they could read or write, the Glovers were all able to do both, some of their fellow passengers could do neither.

The Glover family landed in Sydney, New South Wales and it would appear from a family tree that Elizabeth had other siblings already settled in Australia which they were going to join, one of her brothers died in Chile, an example of the Scottish diaspora spreading its tentacles to the whole world, even far beyond the extent of British colonies. Elizabeth never married and died in Redfern, a Sydney suburb in 1898. Many of her siblings married and their descendants still live in Australia to this day.

Back in Charlotte Sq. the Campbell family remained in occupation long enough to be documented on the 1861 census. Alexander and Catherine Campbell are ten years older; he is still carrying on his brewing business but some of the children had grown into adults by this point in time.

Alexander the eldest son is now 20 years old and serving as an ensign in the 50th Regiment of Foot. The second son, Maurice had died in 1860 at the age of 18 in No. 6. John is now 12 and attending school. Both Catherine and Elizabeth from the previous census do not appear to be at home in the 1861 returns. It is known that Elizabeth married a Mr Ponton and she died whilst still young during a stay the House of the Binns near Linlithgow. She is stated in the paper as being the eldest surviving daughter of Alexander Campbell which sadly implies that Catherine was already deceased as well.

Mr and Mrs Campbell had in that decade from 1851 to 1861 added to their brood, with three children under the age of ten appearing. Eldest amongst these was, Isabella aged 9 followed by William aged 7 years and a little sister Margaret aged 3.

Given the expanded family, Campbell had also expanded his household staff. None of the servants of ten years prior are still in the employ of the family, we know that one went to Australia (Elizabeth Glover) and we can assume that if the others had married then this would lead to the end of their life in service.

In 1861, the 42 year old Arthur Henderson from Thurso is employed, somewhat unexpectedly for a male domestic in the New Town as the cook, like the previous incumbent of the post from ten years earlier; he was probably doubling up with some extra duties as a sort of house steward in the absence of a housekeeper. Henderson is joined by four female servants, Eliza Garrick, 30 from Kirkwall, Isabella and Esther Ross both 24 and both from Ross-shire, possibly (even probably) sisters. Mary Maxwell aged 21 had come to the city from the port town of Grangemouth in Stirlingshire. The youngest servant in the house was the 14 year old son of a fisherman, Alexander Gunn, who had left home in Wick to find work in Edinburgh. He may well have been the scullion boy to the cook and would have been the general underdog in the house upon which all the work that nobody else would do likely landed at his feet.

Other than the census returns Alexander Campbell was referred to numerous times in the printed press. In 1847 he was proving his devotion to God by joining a body called The Sabbath Alliance as a member of their extensive committee. The organisation’s members were sworn to promote the observance of the Lord’s Sabbath. In particular the running of railway trains on a Sunday was seen by the committee as a desecration which needed to be railed against. This was to be brought about, they hoped, by stopping the work of the postal department throughout the entire empire as this was the primary excuse for the operating of railways on a Sunday.

In 1851 he was made an ordinary director of the Commercial Bank of Scotland. Over the years he would go on to collect memberships to the boards of various different organisations based in the city.

He was also a charitable man and is listed for example as making a £5 donation to the cause of the unemployed operatives in Lancashire and other cotton manufacturing districts of England. Also in the 1860’s he was a member of the committee of The Scottish Fire Insurance Company Ltd.

Campbell was also a landlord, as the owner of 186 Canongate his tenant in 1862 was one Charles McLennan who applied to open a public-house at that address that same year. Doubtless as an owner Campbell had no issues with this, another outlet to sell his products would be welcome to the entrepreneur, presumably so long as there was no abuse of the Lord’s Day given Campbell’s membership of The Sabbath Alliance.

Returning to the census we can see that in 1871 Campbell was still living at No. 6 Charlotte Square, by now 63 years of age. At this stage his three youngest children were still living at home with him; Isabella is 19, William is 17 and Margaret is 13.

On the 14th of October 1863 Catherine Campbell (nee Gray-Scott) died at No. 6 Charlotte Square. Leaving her husband Alexander widowed, he never chose to remarry. Catherine was buried in St. Cuthbert’s Kirkyard and there is still a large and elaborate monument to her memory there to this day.

Given the reduced family living in the house, the number of servants had also fallen back to their 1851 number. Again a new census brought with it all new names for the staff as none of those employed in 1861 were still working for the family. When one watches TV programmes such as Upstairs Downstairs or Downton Abbey an impression is created of servants that live out their entire working lives under one family in one place. The truth is that domestic servants, especially in towns and cities lasted in one place only a few years on average. They could be dispensed with for any transgression which their employers were the sole judge of; if maidservants married they were dismissed, if they fell pregnant they were dismissed, if they came in drunk on their day off they could be dismissed, taking food or drink without permission was a sack-able offence. This is not say that any of these things happened at No. 6, they are the extreme possibilities for servants leaving one families employment. Others left to pursue careers in other areas, jobs in industry brought a higher degree of personal freedom, although hard work the days were shorter, they were usually better paid and could continue even whilst married. On the other hand there were career servants who would have found working for the family of a brewer to be something more low level than being in the employ of a titled family for example, and they would have looked for positions in what snobbish servants may have regarded as being a better class of household.

In 1871 the four members of staff looking after the Campbell family were as follows; Agnes Paterson aged 37, listed as the laundress and originating in St Andrews in Fife. Next there was Jane Petrie, a 38 year old housemaid from Orkney. Isabella Reid from North Berwick aged 33 was the cook. Lastly there was Thomas Kay from Lanarkshire who was the 16 year old page (or footman).

In 1881 at the now great age of 73 years old we still find Alexander living in No. 6 Charlotte Square. He was by then joined by only one of his children, William now 27 years of age. There are also grandchildren staying at the house at the time of the census. Feby Matilda Campbell aged 20 is presumably the daughter of Alexander, the eldest son of the owner of No. 6; she is joined by a 17 year old, likely her younger brother, also named Alexander Campbell.

The number of household staff had crept back up by 1881, from four 10 years earlier to five. They were listed as; Eliza Hunter, the family’s 30 year old cook from Cupar in Angus. Eliza Gammell from Leith was their 20 year old laundry maid. The third Eliza, at least their names would be easy for their ageing master to remember, Eliza Henderson a 22 year old from Perth who worked as table maid. Anne Falconer from Lochearn Head was the eldest of the domestics aged 30, she is given on the census as a housemaid but in the absence of a lady of the house, she would likely have been more like a housekeeper in practice than a mere maid. Lastly the below stairs establishment was completed by a 17 year old, the only servant Edinburgh born, Jessie Christie the kitchen maid.

During Alexander Campbell’s time at No. 6 he did have some alterations made to the building. One change from his ownership of which we know was submitted to the Dean of Guild in 1867 by Campbell’s architect, David Rhind. The plan was to include building up the back of the third floor to remove the sloped ceilings and create full sized rooms. Also there was to be a bay window built for the ground floor dining room overlooking the back of the house and supported by cast iron columns, one of which punched through the roof of the scullery below.

In the course of such a long occupancy Campbell must have made other alterations to the house in terms of décor, fixtures and fittings. Fashionable tastes changed a great deal between 1845 and 1887 and he would have given the No. 6 the overall stamp of the Victorian era which the 20th century restoration would later seek to eradicate.

By the time of the next census in 1891 William Campbell has inherited his father’s brewing business and has removed himself from No. 6 Charlotte Square to live at No. 2 Rutland Square only a 5 minute walk away.

Alexander Campbell died on the 12th of June 1887 at Cammo House, a retreat on the edge of the city near Crammond which his beer fortune enabled him to purchase as a getaway place. Both of his houses were disposed of after his death by his son William, No. 6 Charlotte Square was purchased by Mr Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson who moved into the property with his family.

The New Aristocrat: Sir Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson

Like his predecessor as owner of No. 6, Mitchell Thomson started his life out as part of that great band of very prosperous families which by then existed across Britain. They had founded dynasties based not upon chivalric service to the sovereign and power derived from landholdings; their power was new, derived from commerce, industry and its primary product, money. This growing demographic of newly prosperous families had since the industrial revolution been making huge fortunes which allowed them to live in a style befitting the old aristocracy whose tastes and fashions they aped and even attempted to outdo.

The amalgamation of these two types of family had taken its time but by the dawn of the 20th century the traditional upper classes had overcome their opposition to so called “new money” and to show acceptance heaps of hereditary titles were created from the end of the 19th and into the early 20th century, Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson was to be one such newly titled person, bridging the gap between his money making ancestors and his ennobled descendants.

Born in Alloa in early December 1846, he was the youngest son of Andrew Thomson and Janet Mitchell, at this time he was simply Mitchell Thomson, and he later double barrelled his surname.

Janet Mitchell’s father was the entrepreneur William Mitchell, who had been one of the founders of the Alloa Coal Company in 1835. Later William Mitchell became a partner in Ben Line, a shipping firm which took the coal for the Alloa Coal Companies mines out to Canada and returned with timber. So he was reaping profits from all stages of the coal industry from getting it out of the ground, to its shipment to their far flung customers in the Empire. With this fortune base William Mitchell had been able to ensure a comfortable life for his children and grandchildren.

Upon completing his education, Mitchell Thomson was made an apprentice in the family timber importing firm. He became an accomplished businessman and he was offered several directorships during the course of his life. These included a seat on the board of the Bank of Scotland, the Scottish Widow’s Fund Life Assurance Society, the British Investment Trust Company Arizona Trusts and Mortgage Company, the Scottish Reversionary Company Ltd.; the Caledonian Railway and the London Advisory Committee of the Canada Steamship Line Ltd, to name but a few.

In 1876 he was married to Eliza Flowerdew Lowson and together they had one son, she sadly died only one month after giving birth at their pre-Charlotte Square address of 7 Carlton Terrace. He next married in 1880 to Eliza Lamb Cook with whom he had two daughters.

Later, in his 40’s Mitchell Thomson began to seek elected office in his adopted home town of Edinburgh. He failed to be elected to Edinburgh City Council in 1882 on his first attempt but in 1890 he was voted in to a council seat.

Quickly he became an effective politician and public servant. He served on the city’s Gas, Education and Water Commissions. He also became chairman of the Northhill Soup Kitchen committee. He was a trustee and chairman for the George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh.

Mitchell used his business fortune to buy a landed estate at Polmood in Peeblesshire and it was in that same county that he served as a Justice of the Peace. Between 1897 and 1900 he reached his political peak as he served as Lord Provost of Edinburgh. As Lord Provost he was also a representative for Edinburgh to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. He also served on the committee of the Edinburgh branch of the Navy league in the early 1900s.

He was a Unionist politically and he favoured stricter economic control, this is shown by the fact that he was chairman of the Scottish Trade Protection Society (1890s) and later the Tariff Reform League (1900s).

In the same year as he vacated the office of Lord Provost he was raised to a baronetcy by Queen Victoria. It was at this time that he opted to make himself Sir Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson Bt. with the double surname of both his parents, taking into his bloodline the name of his maternal grandfather who had brought him the prosperity which led to this elevation into the pages of Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage.

Again, the census information is useful to get a sense of his household at No. 6 Charlotte Square. The 1891 census return for the house shows Mitchell Thomson as being 44 years of age and a timber merchant, married to Eliza 42. The couple’s two daughters are present; Janet and Violet were 9 and 8 respectively. The eldest child, Mitchell’s son by his first wife is not at home at the time of the census, being aged 14 he would most likely have been away at school.

The family were looked after by a below stairs contingent of four domestic servants; Isabella Dickson Bell was their 46 year old cook from Crammond. The table maid was Margaret Riley aged 33 and hailing from Currie. Janet Martin had come further than the previous two servants to end up in Charlotte Square, as she originated in Morayshire, aged 30 she worked as the laundry maid. The youngest servant was Isabella Forbes at age 25 she too had left home in Morayshire to work as a housemaid in Charlotte Square.

At the beginning of the 20th century the 1901 census reveals that the family were absent from the house at the time of enumeration. No. 6 was occupied solely by servants on this occasion; Margaret Hamilton is the 32 year old cook from Lanarkshire, Jane and Annie Jackson both from North Berwick aged 29 and 17 are both housemaids, one might easily make the assumption that they are related. The last housemaid was Sarah Coutt aged 30 she was originally from North Ronaldsay, the outermost of the Orkney Isles.

The family do not appear on the Scottish census returns for 1901, on further investigation it transpires that he had taken himself off on a tour of the West Indies as a gift to himself now that he was free from the cares of elected office. He purportedly paid a visit to Sir David Wilson the Governor of British Honduras, but he ensured he was back in time to attend the golf championship at Muirfield in June 1901 with Mr and Mrs Henry Asquith.

Mitchell Thomson during the tenure of his term as Lord Provost of Edinburgh. Source: http://curlinghistory.blogspot.co.uk/2010_12_01_archive.html

The family reappear on the 1911 census; Sir Mitchell is listed as being 64 and is no longer given as having an occupation but instead is a man of, “private means”. His wife Eliza, now Lady Mitchell Thomson is aged 62. Both of their daughters remain at home unmarried, Janet and Violet aged 29 and 28 respectively.

In the previous two censuses the house was maintained by four servants, whether the family were in residence or not. By 1811, this Edwardian Baronet had decided that he needed to puff up the size of his household somewhat with more servants heightening the sense of extravagance and comfort in which the family were able to wrap themselves up. On the eve of World War One in the autumn years of the Belle Époque era there was to be no dimming of the lights. To these pampered individuals surrounded by luxury the oncoming downfall of their glorious era, in which Britain had reached the zenith of its world power, was scarcely conceivable.

In 1911 the family had doubled their staff and kept a household of 8 servants; possibly the most since the times of Sir John Sinclair or perhaps more even than he employed. First among these was Edith Bond from England who was a 43 year old lady’s companion. Edith would not have been regarded as a servant as much as part of the extended family.

A woman of more genteel birth than the average paid employee it is likely that Edith had fallen on harder times than she was born to and need to earn a living. She would have been of use to the lady of the house for conversation and perhaps some aspects of personal care such as helping her chose what to wear etc. also acting as a companion to the daughters of the house when they went into the town, although by 1911 they would have a lot more freedom than in the previous century.

The next on the list was the 31 year old Margaret Hogg, a trained hospital nurse. In the absence of children in the house which usually explained the employment of a servant entitled ‘nurse’ the implication is that one member of the family was in need of constant medical attention.

Besides this there was six further female servants all declared on the census return to be general domestics, but they would have had more specific duties than that, one would have been cook, laundry maid, table maid and housemaids, job titles which the family had previously assigned to former serants.

Alexandria Duncan at the age of 59 was the eldest, joined below stairs by Jane Mellis who was 47, Ina Ross was 30, Jessie Whitehead was 31, Mary Fisher was 23 and lastly there was the 18 year old Margaret Bell.

Before the outbreak of the War the family had continued to enjoyed pastime of travelling, they felt free to go anywhere in the world that they liked on account of British influence. They arrived back to Southampton from Buenos Aires in the spring of 1914 and had been in New York in 1912.

It is not known what effect the outbreak of WW1 would have had on the staff of No. 6 Charlotte Square, given that they were all female they would not have been called up to fight but there would have been an expectation and pressure for them to go and work in the factories in place of men, and post war there were a great deal more opportunities for woman, perhaps they would never have come back to the house if they had left service in the course of the war.

After the end of the War in 1918 Charlotte Square became rapidly less residential, a trend which had slowly been happening over the late Victorian and Edwardian era with the invasion of doctors and dentists who opened up surgeries in their dining room flats and lived “above shop” as it were. Soon it looked as though commerce would encroach upon the square fully, but this was not to be the fate of No. 6. In fact it proved to be the “last man standing” of Charlotte Square and it was going to be the final house in the square which was given up as gentleman’s town residence.

North side of Charlotte Square around the early 1900’s when the Mitchell Thomson’s were living there. Source: Scotland’s Places

During his time in the house Sir Mitchell had made some changes as his predecessors had done. It is probable that he had electric lights installed in the house given the time frame of his ownership and going by what is known of the rolling out of that technology in in the city. He made other alterations, such as a third floor billiard room which was top lit and commanded excellent views across the Forth. There were also upgrades to the service aspects of the house, and a food lift was created in order to allow the food to move faster from the basement to the dining room.

Sir Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson’s death came about of a cerebral haemorrhage whilst in hospital on the 15th of November 1918; four days after the armistice which brought to an end the War which had blown apart the world and the society he had grown up with. He would have been in his 71st year of life.

The death certificate was signed by his only son who now succeeded his deceased father as the second Mitchell-Thomson baronet, giving his address as 55 Montagu Square. The new Sir William Mitchell-Thomson Bt. reached high political office in the family tradition established by his father, serving as an M.P. for various constituencies as a Unionist from 1906 until 1932, having served during that time as Postmaster General during the General Strike in 1926 amongst other posts.

In 1932 he resigned from the House of Commons on being elevated to a peerage as Baron of Selsdon by King George V, at which point he was able to enter the House of Lords. This would have undoubtedly made his father proud to have a peerage in the family. As Lord Selsdon he served as the Chairman of the Television Advisory Committee and as such he appeared on the first ever day of BBC Television broadcasting in 1936. Lord Selsdon lived out his days in London and died at home in Grosvenor Square, London in 1938 and he has since been succeeded in his titles by his son and grandson the current and 3rd Baron of Selsdon.

The 4th Marquess of Bute at No. 5 Charlotte Square

In 1903 Sir Mitchell Mitchell-Thomson got a new next door neighbour in Charlotte Square, a 22 year old named John Crichton-Stuart or by title, the 4th Marquess of Bute. On the 11th of July that year the Edinburgh Evening News discreetly reported that that the Marquess of Bute had purchased though his agents, No. 5 Charlotte Square for the sum off £9,500 (over £3.2 million in 2010 terms). This young man’s arrival would turn out to be one of the most significant events in Charlotte Square in the entire 20th century, and it is down to him that Charlotte Square looks as it does today.

Money was no object for this young aristocrat, he as yet had no wife and children to bog down the outgoings and he enjoyed a very substantial inheritance worth over £5 million (comparing that to 2010 earnings a conservative translation of value equates it to £1.7 billion), amongst the highest ever value inheritances in British history. The main source of this super-wealth came from great seems of coal which ran under the family estates in Wales, which had come to the Bute’s by a fortuitous marriage.

For a man like Lord Bute to buy into the square when he had a string of other, grander homes around the British Isles from which to choose; was to make a statement of a new appreciation which was emerging for the New Town at that time. Indeed the very existence of the north side of the square was threatened in in the late 19th century when a proposal was put forward to build a great new concert hall for the city. Luckily, many people railed against the plan, Adam’s designs were becoming to be seen as a masterpiece, in an early example of collective care for heritage buildings.

In 1911 the Bute’s were not at home in No. 5 Charlotte Square but their home was being looked after by a resident staff of; Mary Ellen Groome was a 45 year old housekeeper, joined by two housemaids, Mary Butler, 43 and Elizabeth Gray, 24.

Instead that census shows the 29 year old Marquess at Cardiff Castle, in the city which the 2nd Marquess had founded as a port town to export his coal across the globe. At Cardiff Lord Bute was joined by his wife, five of his young children and a household staff of twenty servants. Amongst this army of retainers were; a butler, 2 housekeepers, Lord Bute’s valet, Lady Bute’s lady’s maid, a nurse, 4 nannies, 2 nursery maids, 3 housemaids, a kitchen maid, 2 still room maids, 2 footmen and a hall boy. Oddly no cook is listed, it may well be that Lord Bute employed a chef with his own cottage on the estate or that he or she was simply absent from the castle at the time of the census. To say that this family lived a little more grandly than the other families owning property in Charlotte Square would have been an understatement.

John Crichton-Stuart, 4th Marquess of Bute. Source: http://www.mountstuart.com/history-and-heritage/bute-family/4th-marquess/

An interesting fact to note about the servants is that 17 of them were Scottish born, 2 French and one Irish. This demonstrates the moveable nature of the household, and many of these staff would travel with the Bute’s as they moved from home to home, usually leaving behind the housekeepers and maids as they would be expected to keep the house in order for the family’s next visit. And indeed the 4th Marquess added additional accommodation to the basement rear of No. 5 Charlotte Square in order to make space for his butler, valet and footmen.

Lord Bute had learned from watching his father that their seemingly inexhaustable wealth could be put to very effective use in the preservation of, and restoration of buildings with strong heritage value. The 3rd Marquess had sympathetic extensions built onto his own Robert Adam house in Ayrshire, Dumfries House; however his true passion had been the mediaeval and gothic. Both Mount Stuart, the family’s ancestral seat on the Isle of Bute and Cardiff Castle were magnificently rebuilt by the 3rd Marquess as the stone embodiment of his wildest dreams, as to what he thought a gothic castle should be.

So the son found a passion for the Georgian revival which was to become very fashionable in the reign of King Edward VII. In No. 5 Charlotte Sq. he ordered his architect A.F. Balfour Paul to de-Victorianise the house, preening back and eradicating the work carried out for former owners. The front room on the ground floor was made into an oak panelled library, and the baluster on the staircase was replaced in carved oak in an early 18th century style. On the first floor the drawing room and parlour were restored to their original proportions and their ceilings were elaborately remodelled. The drawing room ceiling was a copy of an original Adam ceiling from the dressing room of the wife of the 3rd Earl of Bute at Luton Hoo in England.

Upon completion of the restoration the young lord moved in to what is an unmistakably Edwardian interior, but a none the less earnest attempt to recreate what in Lord Bute’s eyes mind an Adam designed house should have for an interior. The works were completed by 1904.

Having set his up home the 4th Marquess decided that it was time to marry. His mother was Gwendolen Fitzalan-Howard, a granddaughter of the 13th Duke of Norfolk. The Norfolk’s were one of Britain’s greatest Catholic families who had survived the English reformation unscathed by being powerful enough to defy the Tudor’s when it came to their faith. The 3rd Marquess of Bute had also converted to Roman Catholicism after marrying Gwendolen; they raised their children as Catholics too.

So it was to Ireland that the 4th Marquess turned when looking for a bride, the place in the United Kingdom where the Catholic faith was far less questionable than in Great Britain. In July 1905 he was married in Kilsaran Catholic Church in County Louth to Augusta Bellingham, the daughter of a local landowner.

The affair was something akin to a mini royal wedding for the locals; the streets were decorated, youngsters given the day off school, the Marquess in Royal Stuart tartan being preceded by 17 pipers. The couple left immediately after the wedding to sail for Scotland and after a honeymoon they set themselves up in No. 5 Charlotte Square where their first child, Lady Mary Crichton-Stuart was born on the 8th of May 1906.

Lord Bute took a break from house buying and restoring during the First World War where he became the only British peer to enlist for service at the rank of private. Perhaps he took a while to recover from the War and that’s which he missed the opportunity in 1918 to make a desirable purchase.

For in 1918 the Bute’s next door neighbour, recently widowed Eliza, Lady Mitchell-Thomson sold No. 6 Charlotte Square for £8,000 (£1.42 million in 2010). The buyers seemed to be a consortium of men; Patrick Murray, William Campbell-Johnston and William Bolden-Wilson. It is unclear what the intention of these men was with the house, but 4 years later it was being sold again.

The Mountjoy Monopoly

On the 1st of June 1922 a company took pocession of No. 6 Charlotte Square from, Patrick Murray, William Campbell-Johnston and William Bolden-Wilson. This firm was called Mountjoy Ltd. And it was a wholly owned family business held by Lord Mountjoy, from whom the business derived its name.

Viscount Mountjoy was only one of several hereditary peerage titles which he held, one of the others being Marquess of Bute. The 4th Marquess had again purchased a house on Charlotte Square through his family property business which was fast becoming the front for the entire Bute estates across the country. It was in the mid 1920’s that Lord Bute/Mountjoy was to rearrange and consolidate his holdings.

In 1922 the Bute Docks and the Cardiff Railway Company (formed by the 3rd Marquess) were absorbed into the Great Western Railway. Between 1923 and 1924 the Bute Collieries were sold off in Glamorgan, Wales. These had been the cash cow that led to the astronomical wealth of the family through the 19th and early 20th centuries, so it is unclear why the 4th Marquess disposed of them at this time; the royalties from extracted coal were retained by the family so they still received a substantial annual income from the mines, perhaps it was worth it not to have to own and run them, just to take a portion of the money as it was made. All the remaining Bute family property was transferred in 1926 into Mountjoy Ltd. The company continued as the property business front for the Bute Estate until recent times but was dissolved by the current Marquess [John Crichton-Stuart, 7th Marquess of Bute] in March 2001.

From 1922 Lord Bute set about restoring No. 6 also, he was happily lodged at No. 5 and had no intention of actually inhabiting No. 6, so his alterations were on a less sweeping scale than had been made at No. 5. None the less all of the Victorian style elements added to the house by the Campbell’s and other non-Georgian adornments made by the Mitchell-Thomson’s were stripped back, and in fact a much more authentic and restrained Georgian feeling was restored to No. 6 compared to the perhaps, over the top No.5 interiors.

The triumphs of the 4th Marquess’s restoration of No. 6 were the neo-Georgian entry hall on the ground floor with its inclusion of an early 18th century fire place which faces visitors as they walk in the front door. The restoration of the first floor drawing rooms took place at this time also with the Victorian double doors between the two rooms being removed and replaced with a single door re-creating the room’s original, symmetrical dimensions. Upon the completion of these restorations the house was rented out to tenants.

Before the 1920’s came to an end, Mountjoy Ltd. also made purchase of No. 7 Charlotte Square upon the exit of the Whyte family from that address in 1927. This purchase gave the Marquis control of the three house wide centrepiece of the Adam “palace front” on the north side of the square. He used Mountjoy Ltd. to complete his string of purchases by later adding No. 8 to his collection also.

Strength in numbers it seemed gave Lord Bute the clout necessary to restore not just the interior of his houses to something of their former Georgian appearance but he was also able to pull together a collective effort to restore the north side of the square externally to try and recreate Adam’s original vision. Many of the houses had been altered in such an untidy way that there was no longer any uniformity of the façade at all, each individual house was clearly demarcated by the different windows or doors or dormer windows which no longer matched their next door neighbour.

Nos. 5 and 7 flanking No. 6 had both in 1871, under the auspices of their then owners, undergone alterations to drop the drawing rooms windows from their original level down so as to make them floor to ceiling. Additional to this was the removal of the thin columns of astragals either side of the venetians which No. 5 and 7 originally had as their first floor windows which were immediately next to No. 6. Both of these houses also had ugly box dormers installed in 1889, the only saving grace was that these separate owners were seemingly working in tandem to maintain some air of symmetry. Suggesting that they were well aware as to the damage they were causing to the harmony of Adam’s design, but they were not interested enough to stop making these modifications.

Part of the 4th Marquess’s restoration included the correction of the first floor window heights, the restoration of fanlights and astragals which the Victorian era had seen removed. Crucially he ordered the demolition of the dormer windows poking out of the roofs of the houses. Balfour Paul was set to work on the interiors of No. 7 as he had been in the early 20th century at No. 5, this restoration cost No. 7 two original dining room recesses which were thought to be Victorian additions, Balfour Paul was perhaps too thorough in his work and not thorough enough in his research.

Nos. 5, 6 and 7 Charlotte Square returned (almost) to their original appearance, this was completed in the early 1930’s but this shot dates for the 1950’s or 1960’s. Source: http://www.scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/search_item/index.php?service=RCAHMS&id=114512&image_id=SC460249

Once architectural harmony had been regained to the best of the Marquess of Bute’s knowledge and opinion he moved to secure his legacy by helping to create one of the first conservation orders in Scottish history. The Edinburgh Town Planning (Charlotte Square) Scheme Order, 1930 was enacted by the invocation of the 1925 Town Planning (Scotland) Act. The establishment in 1931 of the National Trust for Scotland would be of assistance to a private individual like the Marquess in spreading his message of heritage conservation through a public body with interested and influential stakeholders. Some decades later the 4th Marquesses grandson, the 6th Marquess, would become President of the National Trust for Scotland and undoubtedly the latter brought as much to that role as he did in no small part owning to the influence of his grandfather.

The 4th Marquess died on the 25th of April 1947 at the age of 65 at his ancestral seat of Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute. The Evening Telegraph report elected to describe his financial activities the weekend after his death. The Marquess had, “sold half the city of Cardiff for £2 million,” including, “20,000 houses, 1,000 shops and various theatres and cinemas”, his Welsh seat of Cardiff castle was possessed of a, “gold plated staircase”.

Prior to the nationalisation of coal royalties he was earning £117,000 (£18.3 million in 2010) per annum. His lands in Britain at the time of his death still extended to 117,000 acres upon which he had 6 stately homes in various locations. A castle in Spain and extensive lands in Morocco where he was the greatest foreign landowner and he commissioned the luxury El Minzah hotel in 1930, which is decorated in the Spanish Moroccan style, and can still be found today overlooking the Straits of Gibraltar in the centre of Tangier.

In all the 4th Marquess left an estate worth around £60,000,000 (£5 billion in 2010) and so despite two world wars, a great depression and the introduction of cripplingly high taxes in the post war period, not to mention the loss of revenue from the now state owned coal royalties he was still one of the richest people in Britain. He was by far and away Charlotte Squares wealthiest ever resident, even including the overthrown French monarch who had lived at No. 6 for a time in 1832.

After 4th came the 5th Marquess; another John Crichton-Stuart, the new Lord Bute preferred to make his Edinburgh home in No. 6 Charlotte Square and moved their Edinburgh base next door into the centre house. At this point No. 6 can claim to have become Bute House, even if that term was still not yet in common usage.

Unsurprisingly, the 5th Marquess received a rather heart sinking tax bill for inheriting such a huge fortune only two years after the end of the World War II, he was expected to pay 75% to the Treasury, or in monetary terms £45 million out of the £60 million estate value. That was just the beginning; there were tranches of other taxes and fees to deal with too. Being asset rich and cash poor was to the story of the British aristocracy through the second half of the 20th century. The total inheritance which the 5th Marquess received after all duties had been paid was the comparatively minuscule amount of £264,000 (£22.3 million). Bute’s have proven to one of those families who dealt with the 21st century and held on to much of what they had held in the past.

Soon after the death of his father the 5th Marquess gave up Cardiff Castle to the city of Cardiff and it is now operated by Cadw (the Welsh equivalent of Historic Scotland or English Heritage) and open to the public. Despite the fact that he had offloaded this significant estate he was also the purchaser of St. Kilda, an archipelago of Scotland’s North Atlantic coast. His acquisition was based on a love of ornithology and these islands were the perfect place to further his studies, in his will he left St. Kilda to the National Trust for Scotland.

By the 1950’s there were very few houses in Charlotte Sq. actually being lived in as complete townhouses, Bute House was the last one to be used in the traditional old style for which it was intended. From 1948 Mountjoy Ltd. (the 5th Marquess of Bute) had leased his late father’s former residence of No. 5 Charlotte Sq. to the National Trust for Scotland who had just moved out of offices in Gladstone’s Land on the Lawnmarket. And to the other side of Bute House, No. 7 had been let since before 1930 after its own restoration was completed to Whytock and Reid; the now sadly defunct Edinburgh based cabinet maker, drapers and antique dealers. The only reason they had been purchased by the 4th Marquess was to enact his Adam revival restoration of the square, he had never had any intention using them personally.

John Crichton-Stuart, 5th Marquess of Bute. Source: http://www.mountstuart.com/history-and-heritage/bute-family/5th-marquess/

The 5th Marquess died at his family’s ancient seat of Mount Stuart on the 14th of August 1956, another premature death as his father and grandfather were not very old when they had died. This Lord Bute was only 49 years old and was taken by a particularly serious bout of pneumonia.

No. 6 in the Care of the Nation

The 5th Marquess was succeeded by his eldest son and name sake, John Crichton-Stuart 6th Marquess of Bute. Upon Lord Bute’s death in 1956 he left an estate valued at £139,472 (£6.7million in 2010) upon which duties payable totalled at £111,577 (£5.37 million). The mighty industrial fortune enjoyed by the 3rd and 4th Marquesses was now gone, and the next decade or so would be a financial balancing act for the 6th Marquess of Bute to determine what had to give, in order to keep as much of his family heritage intact as possible.

Negotiations took place at length between the trustees of the 5th Marquess’s estate and the Inland Revenue over the repayments of these death duties. Falkland Palace had already been placed in the care of the National Trust for Scotland in 1952 and in order to be able to meet the payment of the inheritance tax more property would have to be given up. And so it was a full ten years after the death of the 5th Marquess, that in March 1966, the trustees under settlement between the 6th Marquess and his solicitors disposed of Nos. 5, 6 and 7 Charlotte Square on behalf of Mountjoy Ltd, with the acquiescence of the Inland Revenue, to the National Trust for Scotland. It is unclear why No. 8 was not also given over at the same time; it was possibly sold prior to 1956.

Upon giving over these properties the 6th Marquess had certain ideas for how his former three houses should be used. He was keen for the National Trust for Scotland to maintain its headquarters at No. 5. Suddenly finding that they owned the house which they had been renting since 1948 the Trust were more than happy maintain themselves at No. 5, remaining until 1999 before vacating to the more spacious suite of houses on the south side of the square known properly as Wemyss House (after the 12th Earl of Wemyss a former President of the National Trust for Scotland), but known more often as “No. 28”, as it was through No. 28’s door that the five house complex was entered.

No. 7 was to continue being rented out by Whytock and Reid, from the Trust as it had been from Mountjoy Ltd; until 1973 when their lease expired and the Trust decided that it would be restored into a public visitor attraction displaying the interiors of a ‘typical’ Edinburgh New Town house c.1800 [known as The Georgian House]. This idea may have originated from the 6th Marquess and been one of his intentions when handing the house over so as that the National Land Fund would accept the terms.

A more controversial request from the 6th Marquess was that he was concerned that Bute House itself was to remain as a ‘home’. The problem here came from the National Land Fund, who were key players in the negotiations which saw the properties transferred to the Trust. They insisted that they would support nothing if there was not at least some degree of public access.

: John Crichton-Stuart, 6th Marquess of Bute. Source: http://www.mountstuart.com/history-and-heritage/bute-family/6th-marquess/

A solution was found in the idea, which had long been touted in Edinburgh, for an official residence for the Secretary of State for Scotland. To provide the secretary with a bolthole whilst in the city and where he or she could entertain key people and thereby selected members of the public would be able to access the interior of Bute House. This seemed to work and a proposal and plans pressed ahead for the setting up of Bute House.

The Bute House Trust was set up to oversee the conversion of the house into its use for the Secretary of State and the National Trust for Scotland leased the house to the newly formed Trust for a peppercorn rent. The Chairman of the trustees of this new Bute House Trust was none other than the 6th Marquess of Bute, so in a way he left No. 6 but not really.

The trustees were responsible for raising the £30,000 spent by 1970 (£653,000 in 2010), which it took to make alterations, re-decorate and re-furnish the house to make the house fit for its new purpose. As well as spending money, many individuals and organisations were generous with loans or gifts of furniture from a substantial and valuable loans of collections from Althea Dundas-Bekker at Arniston House, which the National Trust for Scotland kept for over 20 years and much of it placed into Bute House, down to the gift of a colour T.V. set from Scottish Television.

By June 1970 the house was ready for habitation once again, some of its collection highlights at that time were an Allan Ramsay portrait of the 3rd Earl of Bute (ancestor of the 6th Marquess who had been Great Britain’s first Scottish prime minister), a specially designed rosewood sideboard created in 1973 especially for the Bute House dining room by Edward Barnsley, one of the 20th centuries leading furniture designers. Also on loan were four Chippendale chairs in red damask with a matching Sheraton settee.

This arrangement between the serving Secretary of State for Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland continued, facilitated by the Bute House Trust, until the year 1999. It was at this stage that the Scottish Parliament was reconvened after an almost 300 year absence from Edinburgh and consequently Bute House was promoted from the pied-a-terre of a London based cabinet secretary into the permanent base of the leader of Scotland’s new devolved administration.

The Drawing Room of Bute House in 1970 as it was set up in readiness for the use of the Secretary of State for Scotland.

Bute House in the Devolution Era

Rumour has it from within the Scottish Government (it may or may not be true) that Bute House was not the first choice of the Civil Service when coming to decide where they were to lodge the newly created First Minister of Scotland, after all No. 6 was already the home of the Secretary of State for Scotland. The government owned the Governor’s House, perched atop Calton Hill clinging to the edge of the cliff face above Waverly Station. That house seemed to meet the civil services criteria, who realised that making that house into lodging would be the most cost effective thing for the tax payer as there would have been no rent involved. However, Donald Dewar the first First Minister in devolution Scotland, was aghast at the prospect of being housed in a mini-castle in such a prominent location in central Edinburgh. That would have done his supposed left wing credentials no favours. Instead he pushed for the eviction of his Labour party colleague, the Secretary of State for Scotland, who basically had a title but no real work to do anyway in the wake of a new Scottish executive. At least that is the hearsay behind the choice of residence.

Governor’s House, First Minister Dewar’s apparently early refusal of this house led to Bute House becoming the FM’s official residence.

What is fact is that on the 17th of May 1999 Donald Dewar was appointed First Minister of Scotland by the Queen during the course of a discreet private meeting in the Morning Drawing Room of Holyrood Palace. They were surrounded by furniture that was commissioned for King Charles X of France when he was lodged at the Palace in the immediate aftermath of his overthrowing from the French throne. King Charles X was something they both had in common, as of that day; they both lived somewhere that King Charles X had called home for a time.

The setup of Bute House was finalised (for the time being) in 1999 and has changed relatively little in how it has been used since then. The basement is devoted to housing the First Minister’s staff, formers pantries and servants rooms turned into offices full of computers with strip lighting in the ceiling and broadband cables on the floor.

The ground floor has changed the least in purpose over the centuries; the large dining room at the rear of that level has even managed to retain its original Georgian cornice and is used really only for official dinners. Connecting to that there is a onetime butler’s pantry which has now been made into a well equipped kitchen to serve the main dining room.

The drawing room on the first floor overlooking the square is where the first minister receives guests and entertains official visitors, sumptuously furnished with many fine paintings on loan from the National Galleries of Scotland.